In a groundbreaking intersection of art and technology, a new frontier is emerging for visually impaired artists. The concept of "light-feel painting" – where infrared thermal imaging is translated into tactile sensations – is challenging long-held assumptions about the limitations of blindness in visual arts. This innovative approach doesn't just adapt existing techniques; it creates an entirely new medium that speaks to the unique perceptual experiences of those without sight.

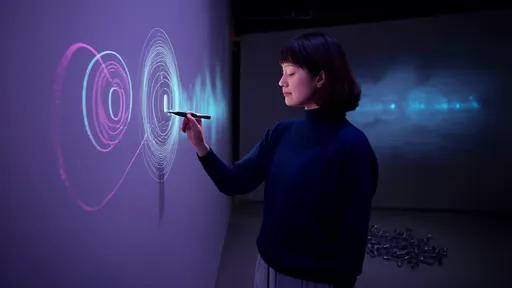

The process begins with specialized thermal cameras capturing heat signatures from living subjects or environments. Unlike conventional photography that relies on visible light, these infrared images map temperature variations across surfaces. What makes this technology transformative is its subsequent conversion into physical textures that can be explored through touch. Raised surfaces correspond to warmer areas while depressions indicate cooler zones, allowing blind artists to "see" through their fingertips what others perceive with their eyes.

Several pioneering artists have embraced this medium with astonishing results. One creator described the experience as "painting with the warmth of life itself," using heated tools to deliberately alter thermal patterns before capture. The resulting artworks, when converted to tactile formats, reveal compositions that play with thermal contrast much as traditional painters manipulate light and shadow. These pieces often startle sighted viewers with their sophisticated understanding of spatial relationships and emotional resonance.

The technology behind this movement stems from military and medical infrared applications, repurposed for artistic expression. Advanced 3D printing techniques create detailed textured surfaces from thermal data, with varying heights corresponding to temperature gradients. Some systems incorporate dynamic elements – small heating components that allow the artwork to change when touched, creating an interactive dimension impossible in conventional art.

Educational institutions for the blind are beginning to adopt these methods, reporting unexpected benefits beyond artistic training. Students engaging with thermal-tactile art demonstrate improved spatial reasoning and heightened environmental awareness. The medium provides a concrete way to understand abstract concepts like energy flow, solar radiation, and even the emotional warmth conveyed in human interactions.

Critics initially dismissed thermal-tactile art as a mere scientific curiosity, but recent exhibitions have silenced skeptics. The works command attention not as novelty items or disability accommodations, but as legitimate contributions to contemporary art. Galleries report that sighted visitors often prefer experiencing these pieces with closed eyes, discovering new dimensions of perception through touch rather than vision.

The psychological impact on participating artists proves equally profound. Many describe the process as revelatory – finally accessing a visual art form on their own terms without dependence on sighted interpreters. One artist remarked, "For the first time, I'm not translating someone else's visual language. The heat patterns speak directly to my hands in a way eyes could never understand."

Commercial applications are already emerging from this artistic movement. Architectural firms employ similar tactile thermal models to help blind clients experience building designs. Environmental scientists collaborate with tactile-thermal artists to create accessible representations of climate data. The fashion industry explores thermal-reactive fabrics that change texture based on body heat, inspired by these artistic innovations.

As the technology becomes more accessible, grassroots communities of blind creators are forming worldwide. Online platforms allow artists to share thermal image files for tactile printing, creating a new kind of collaborative art that transcends physical distance. Some collectives specialize in "thermal portraits," capturing the unique heat signatures of individuals as intimate personal artworks.

The philosophical implications of this movement ripple beyond the art world. By demonstrating that visual art doesn't require vision in the conventional sense, these creators challenge fundamental assumptions about perception and creativity. Their work suggests that art resides not in the medium itself, but in the human capacity to transform sensory information into meaningful expression – whether through eyes, fingertips, or the subtle perception of warmth.

Looking ahead, researchers are developing more sophisticated interfaces that incorporate additional environmental data like airflow or moisture levels into tactile artworks. Early experiments with thermal video – sequences of tactile frames that change over time – hint at possibilities for dynamic tactile "cinema." As these technologies mature, they promise to further dissolve barriers between sighted and blind artistic expression.

What began as a technical experiment has blossomed into a vibrant artistic movement that redefines creative possibilities. The thermal-tactile art revolution demonstrates that human creativity will always find new pathways, regardless of physical limitations. In the hands of these pioneering artists, infrared radiation becomes a brush, heat signatures form the palette, and the human capacity for expression finds yet another way to illuminate our shared experience.

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025