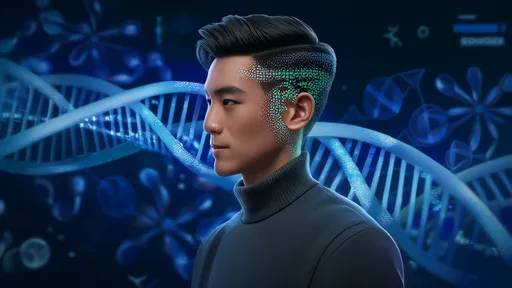

In an age where science and art increasingly intersect, a provocative new frontier has emerged: the artistic rendering of genetic data. What began as clinical biometrics has evolved into a controversial creative practice—genetic portraiture. These visually striking interpretations of DNA sequences raise profound questions about consent, privacy, and the very definition of human identity in the digital era.

At prestigious galleries from London to Tokyo, visitors now encounter vibrant swirls of color purportedly mapping an individual’s genomic blueprint. The process involves translating nucleotide sequences into visual patterns through proprietary algorithms, creating what proponents hail as "the ultimate self-portrait." Yet behind these dazzling exhibitions lies an ethical minefield that the art world is only beginning to navigate.

The commercialization of biological identity represents perhaps the most immediate concern. Unlike traditional portraits where subjects consciously pose, genetic artworks often utilize DNA samples originally collected for medical testing or ancestry services. Many donors remain unaware their biological data has been repurposed as aesthetic commodities selling for five-figure sums. This secondary market operates in a regulatory gray zone, with consent forms from testing companies frequently containing buried clauses about "artistic applications."

Cultural critics point to deeper philosophical tensions. The reduction of human complexity to algorithmic visualizations echoes troubling historical practices of biological categorization. While artists insist these works celebrate genetic diversity, some ethicists warn they risk reviving pseudoscientific physiognomy—the discredited practice of judging character by physical features—in digital guise. The very act of assigning visual representations to invisible genetic markers constitutes an interpretive leap that makes many scientists uncomfortable.

Privacy implications extend beyond the individual. Familial genetic connections mean one person’s "portrait" inevitably reveals information about relatives who never consented to participation. Recent scandals involving law enforcement accessing genealogy databases have heightened these concerns. Unlike conventional art that decays, genetic data remains perpetually identifiable—and vulnerable to advancing analytical techniques.

Defenders argue that genetic art democratizes science, making abstract concepts tangible to lay audiences. Some exhibitions deliberately anonymize donors, focusing on universal human similarities rather than individual differences. Certain artists collaborate directly with subjects, incorporating personal narratives to contextualize the biological data. These approaches attempt to balance aesthetic innovation with ethical responsibility.

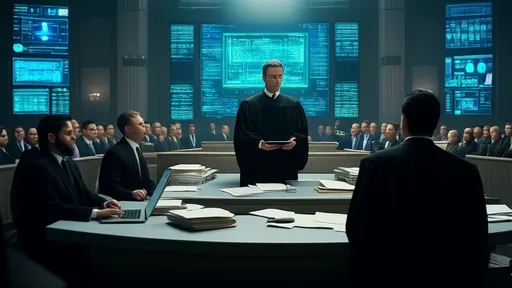

The legal landscape struggles to keep pace. Copyright law remains unclear whether ownership resides with the DNA donor, the sequencing company, or the interpreting artist. International disparities in biobank regulations create loopholes for "ethics shopping." Proposed frameworks suggest treating genetic information like bodily organs—inalienable personal property that cannot be commercially traded. But enforcement proves challenging in our borderless digital economy.

Emerging technologies compound these dilemmas. AI generative tools now create synthetic genetic portraits without any physical DNA sample, blurring lines between representation and fabrication. Meanwhile, CRISPR gene-editing advancements mean future artworks might not just depict genes but actively alter them for aesthetic purposes—a scenario that bioethicists describe as "playing deity with double helixes."

Perhaps the most unsettling question concerns perception shifts. As genetic portraits enter mainstream culture, will we begin to "see" each other through the lens of genomic aesthetics? The history of art demonstrates how visual representations shape social hierarchies—from Renaissance portraiture affirming nobility to colonial ethnography reinforcing racial stereotypes. The power dynamics embedded in who gets to interpret genetic data, and how, demand rigorous scrutiny.

Galleries now hosting genetic art exhibitions increasingly employ bioethicists alongside curators. Some institutions have established review boards resembling hospital ethics committees. These developments suggest the art world recognizes it cannot rely solely on creative freedom arguments when handling biological essence. Yet voluntary guidelines remain inconsistent, and many private collectors operate without oversight.

The conversation extends beyond Western art capitals. Indigenous communities—long exploited by scientific research—are asserting sovereignty over genetic data derived from their populations. Some have begun creating their own genomic art traditions, reclaiming narrative control. These projects emphasize communal rather than individual ownership, challenging the very notion of "portraiture" as a personal representation.

Techno-optimists envision a future where everyone possesses and profits from their genetic artwork. Blockchain solutions promise to establish clear provenance and compensation chains. Virtual reality platforms could enable interactive exploration of one’s own genomic landscape. But these utopian visions must contend with existing power asymmetries in who can access and understand complex biological data.

As museum directors report growing collector interest in genetic portraiture, the market pressure threatens to outpace ethical deliberation. The parallels with early photography are instructive—a technology initially viewed as intrusive and dehumanizing that eventually transformed artistic expression. Genetic art may follow a similar trajectory toward normalization, making urgent today’s debates about its boundaries.

What remains undisputed is that human DNA constitutes our most intimate information. Its transformation into aesthetic commodity demands frameworks that respect both creative liberty and human dignity. The challenge lies in developing an ethics of representation adequate to an era when science can render the invisible visible—and art can sell what was never meant to be sold.

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025