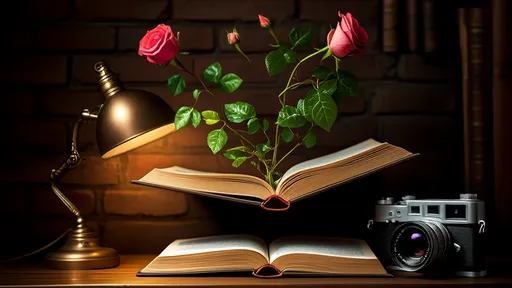

In an era where time-lapse photography has become commonplace, a groundbreaking project has emerged that redefines our perception of botanical time. "The Century-Long Lens", an ambitious photographic experiment, captures plant growth across generational timescales using frame intervals measured in months rather than seconds. This extraordinary endeavor challenges not only technical limitations but also our fundamental understanding of vegetative life.

The concept originated from an accidental discovery in 1923 when botanist Dr. Elias Thornfield noticed peculiar patterns in glass plate negatives left forgotten in his greenhouse laboratory. What began as spoiled exposures revealed subtle changes in fern specimens over eighteen months. This serendipitous observation sparked a century-spanning investigation into ultra-slow motion plant photography that continues to this day.

Modern iterations of the project employ specially designed growth chambers with robotic camera systems. These climate-controlled environments maintain perfect conditions for both plant development and photographic consistency. The current flagship installation at the Berlin Botanical Garden contains a 190-year-old oak sapling that has been photographed approximately 380 times since its planting in 1934, creating what researchers call "a botanical flipbook of the atomic age."

Technical challenges in such long-duration photography are immense. Early practitioners struggled with fungal growth on lenses, while contemporary teams battle digital obsolescence - the project has outlived seventeen different camera technologies. Specialized film emulsions were developed in the 1950s to resist degradation, and modern systems use quartz-encased sensors with self-cleaning mechanisms.

The resulting images reveal phenomena invisible to conventional observation. Time-lapse sequences show trees performing what appear to be deliberate, slow-motion dances as they follow decades-long growth patterns. Root systems display complex decision-making processes when encountering obstacles, sometimes taking years to redirect. Most remarkably, the photographs capture evidence of generational memory in plants, with specimens demonstrating learned responses to environmental challenges across multiple growth cycles.

Beyond scientific value, the project has inspired artists and philosophers. The "Decadal Portraits" series, which documents individual plants across human lifetimes, has been exhibited worldwide. Critics note how these images collapse our anthropocentric perception of time, forcing viewers to reconcile with timescales beyond human experience. A famous sequence showing a bamboo grove's century-long expansion was described by one art historian as "watching continental drift in miniature."

Current research focuses on developing predictive models from the accumulated visual data. By analyzing growth patterns across multiple plant generations, scientists hope to forecast botanical responses to climate change. The project's database now contains over 14 million images representing 1,200 species, creating what may be the most comprehensive visual record of plant life ever assembled.

As the initiative enters its second century, new technologies promise even more remarkable revelations. Quantum imaging sensors capable of detecting subtle biophotonic emissions may soon allow researchers to visualize plants' chemical communication systems across time. Meanwhile, experimental stations have been established in extreme environments from Arctic tundra to tropical rainforests, expanding the project's scope to document vegetation responses to diverse climatic conditions.

The philosophical implications continue to resonate. These glacial-paced observations challenge our definitions of movement, behavior, and even consciousness in the plant kingdom. What appears as stillness to human eyes becomes dynamic activity when viewed across appropriate timescales. The project's founding principle - that understanding requires observation at the subject's natural pace - has influenced fields from microbiology to cosmology.

Public engagement remains a priority, with live streams from several growth chambers available online. The most popular feed follows a century-old bonsai tree that has been photographed approximately twice yearly since 1927, creating a mesmerizing sequence of gradual transformation. Educational programs use these resources to teach concepts of deep time and ecological patience to new generations.

Looking ahead, curators plan to establish permanent archives capable of preserving the collection for millennia. Specialized storage facilities are being constructed in geologically stable locations, with some designed to maintain integrity for projected timespans exceeding the lifespan of the plant subjects themselves. These efforts ensure that future researchers may continue studying these botanical timelines long after the original observers are gone.

In an age of instant gratification and accelerating technological change, "The Century-Long Lens" stands as a testament to the value of sustained observation. It reminds us that some truths reveal themselves not in the flash of inspiration, but through the patient accumulation of glimpses across generations. As the project's motto states: "To see the forest, we must watch each tree grow."

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025